Separation of Church and State in America

What the Separation of Church and State in America Really Means, and Why it Matters

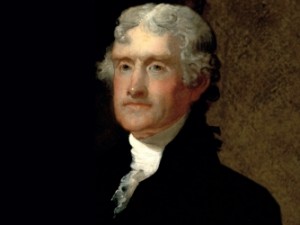

One of the most interesting details of the controversy over the constitutional separation of church and state is that the term never appears in the Constitution itself. The term “separation of church and state” is part of an address made in writing by Thomas Jefferson, which was delivered to the Danbury Baptist Association. Baptists hold the separation of church and state as one of the central themes of their theology and traditions, and were worried about the encroachment on their rights by members of other churches a the state level.

Baptists were a minority in Connecticut, and they were suspicious of the Congregational majority’s motives in drawing up the constitution of the State of Connecticut without any mention of freedom of religious observance. They feared that the melding of religious and political power into one entity that they had thrown off in the person of George III of England could be recreated in their state unless it was explicitly forbidden. Thomas Jefferson was newly elected as the third president of the United States, and as one of the primary authors of the United States Constitution, the Danbury Baptists hoped he could shed some light on the purpose behind several of the entries in the Bill of Rights.

Interestingly, Jefferson’s reply is less than half as long as the Danbury Baptist Association’s letter asking for his help and guidance in the matter. Because the reply is so closely written and unambiguous, it has been relied upon as a key document in interpreting the first, ninth, and tenth amendment to the US Constitution. In it, Jefferson quotes the constitution while appending an explanation that has become one of the most quoted and hotly debated documents in American history:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legislative powers of the government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature would “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church and State.

When the authors and signatories of the Constitution placed limits on the power of the government by adding the Bill of Rights, many of their contemporaries objected. They felt that any list of rights suggested that these were all the rights that a citizen was entitled to. The idea that rights were granted to citizens by the government bothered them, and for that reason, the Ninth and Tenth Amendments were added to specify that rights that were not mentioned in the federal constitution should be assumed to be reserved at the state level, and beyond that, to individual citizens.

This is what prompted the Connecticut Baptists to seek affirmation of their rights as a religious minority to the head of the federal branch of the government. They believed, and Jefferson re-affirmed, that the federal government was designed to remain neutral in matters of religious conscience. They hoped that Jefferson could throw his weight into the conflict that might arise at the state level over the same rights and privileges. Jefferson’s phrase of a wall of separation between church and state is much stronger and more sharply defined than the terms used in the First Amendment, which was covering more ground about freedom of speech and other rights, and somewhat blunted its message about religious freedom.

A survey of the writings of prominent Americans involved in the government at the time would have found as large a fear of the government meddling in religious affairs as religions meddling in government affairs. Benjamin Franklin, in particular, wrote that he felt that any particular religion was always based on its appeal to its adherents, and if it lost its appeal, the particular sect should fade away to be replaced with another one. He believed that an appeal for a civil power to enforce religious dogma was a sign of a bad religion, unable to stand on its own merits.

It’s easier to understand the founding fathers views on the separation of church and state if you understand the term Deism. The Declaration of Independence and the following documents that make up the working framework of the United States government are filled with terms like Nature’s God, the Creator, the Supreme Judge, and George Washington’s favorite, Divine Providence. These are all terms that are favored by Deist. A Deist is someone that believes in a Divine Creator who made the universe and determined the laws of nature that ruled over it. A Deist doesn’t believe that there is a God that meddles in human affairs, or supernatural manifestations of a God, or basically that any man’s opinion on what God is trumps another man’s opinion. These are ideas that were very popular during that time period, often called the Enlightenment.

When George Washington was sworn in as the first president, there was a delay in the ceremony because no one had brought a Bible to swear on. Swearing on a Bible was the traditional way to aver that you were testifying to a higher authority that what you are saying was true, and since Washington was swearing an oath, it was natural for him to take it on a Bible. None of the founding fathers would have said that swearing on a Bible means that the Bible itself is a rulebook that is being followed. The president is simply testifying in front of a higher power that he will faithfully follow the rules drawn up by a duly elected government based on secular legislation.

During the 1950s, the government added many references to God on currency and ceremonial rites like the Pledge of Allegiance. In the intervening years, these have been viewed by many as an encroachment on the separation of church and states, especially as more people identify themselves as atheists, and would prefer no reference to God or religion of any kind in any public forum or document. Legally, these references to God have been judged to be a form of oath taking, not a directive for citizens to worship any particular version of God, or even to acknowledge that there is a God at all. Very finely drawn distinctions have been made between referring to God and religious observance in historical terms rather than in a spirit of worship or reverence. The Supreme Court has ruled that displays of the Ten Commandments from the Bible can be displayed in public places like courthouses, but only because they are part of the tradition of jurisprudence, not because their religious significance is paramount. Another example of where the separation of church and state comes into play is in the context of drunk driving or criminal cases in general. For years, the courts ordered defendants to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings as condition of bail or as part of a sentence in court. However, that changed due to the fact that Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is an organization that relies on the principals of God and religion in the treatment of alcoholism. Therefore, for the court to order attendance at AA meetings, it was by default sanction the religious aspects of AA which was violation of the separation of church and state, according to Marin County DUI Defense Attorney Michael Rehm. In most courts now, they order the defendant to attend “self-help” meetings, whether those are AA meetings, or another secular organization.

Our founding fathers would probably be confused and disconcerted by legislation like the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, passed in 1997 and signed by President Bill Clinton. It tried to allow exceptions to following all laws if they were in conflict with legislation, but in practice it has become almost unworkable. The bill was found partially unconstitutional at the state level, but it’s still in effect at the federal level. Various state governments have enacted their own versions of it since. By trying to enumerate specific ways in which religious adherents can avoid being forced to follow federal and state laws due to their convictions, the framers of the Constitution would probably have seen it as like trying to amend the Bill of Rights with thousands of additional exceptions. It’s likely that they would have desired that laws be drawn up on a secular basis, and no religion would serve as an exception to following them.

Follow

Follow